EPA Issues Revised Anti-Tampering Enforcement Policy and Requests Comments on Catalytic Converter Enforcement Policy

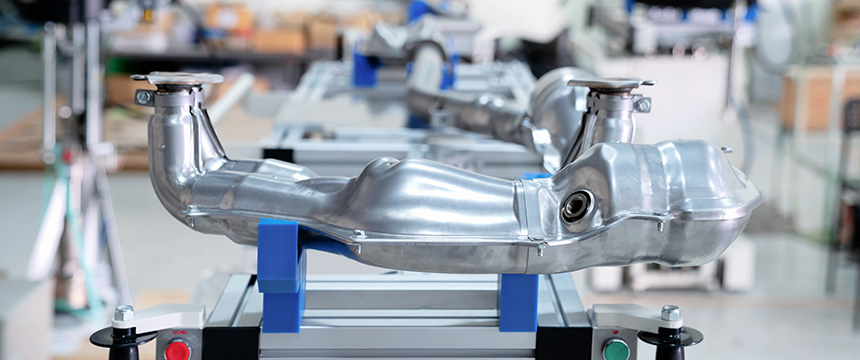

Several years into EPA’s mobile source enforcement initiative, the agency recently issued an updated enforcement policy addressing vehicle and engine tampering and aftermarket defeat devices (the “Tampering Policy”). The Tampering Policy was posted to the EPA Office of Enforcement & Compliance Assurance’s website in late November, along with a separate pre-publication notice soliciting comment on EPA’s 1986 enforcement policy related to catalytic converters. EPA issued the revised Tampering Policy on the heels of a recent EPA report indicating that emission controls have been removed from more than 550,000 diesel trucks in the last decade, resulting in hundreds of thousands of tons of excess emissions over the vehicles’ lifetimes. Given these enforcement efforts, the revised Tampering Policy has meaningful implications for those that manufacture, sell, or install certain aftermarket parts or that service engines and vehicles, including considerations for testing, recordkeeping, marketing materials, and labeling for aftermarket parts.

Updated Tampering Policy

Section 203(a)(3) of the Clean Air Act prohibits tampering with emission controls and manufacturing and selling products that defeat or bypass emission controls. The Tampering Policy addresses these prohibitions, consolidates a number of historic EPA enforcement policies in this area, and supersedes EPA’s previous 1974 guidance (known as Memorandum 1A) related to tampering and defeat devices. The overarching policy underlying Memorandum 1A is that EPA typically will not take enforcement action respecting engine tampering if a person (or company) has documented a “reasonable basis” that its conduct (including the manufacture, sale, or installation of a part) will not adversely affect emissions.

In 2017, EPA identified efforts to stop tampering with engines and vehicles and to stop the manufacture, sale, and installation of defeat devices as an ongoing National Compliance Initiative, with enforcement primarily directed at: (1) aftermarket parts manufacturers; (2) companies that modify emission controls on commercial fleets; and (3) service centers that remove emission control equipment. In connection with this initiative, EPA first solicited stakeholder feedback on a revised tampering and defeat device policy in 2018. The newly revised Tampering Policy maintains the overarching policy position of Memorandum 1A, but provides a more detailed framework for compliance, captures additional vehicles and equipment in its scope, and accounts for advancements in technology.

The Tampering Policy applies to all motor vehicles and engines, including non-road vehicles and engines, with limited exceptions (for example, vehicles and engines used solely for competition, along with parts manufactured/sold for those applications, are excluded from regulation). While EPA does not have specific authority to regulate the sale of aftermarket parts under the Clean Air Act, it can take action to ensure that certified engines, vehicles, and equipment remain in compliance with emission standards. The Tampering Policy addresses aftermarket parts in addition to vehicles, engines, and equipment through that authority.

The centerpiece of the Tampering Policy remains virtually unchanged from Memorandum 1A – namely, that EPA typically will not take enforcement action if a person has a documented “reasonable basis” that the conduct (including the manufacture, sale, or installation of a part) will not adversely affect emissions. However, the updated policy offers regulated industry more clarity on what constitutes a “reasonable basis.”

What Constitutes a “Reasonable Basis”

EPA’s guidance has long stated that the agency would exercise enforcement discretion in the context of aftermarket part manufacture, sale, and installation where the individual has a “reasonable basis” that the conduct will not adversely affect emissions. However, until now, that guidance was broad and arguably out-of-date at the federal level. Since EPA first issued its guidance in this area in 1974, other states have implemented their own programs for the regulation of emission-related aftermarket parts, including specific certification/exemption procedures. For example, California requires that manufacturers obtain pre-approval through an Executive Order for all aftermarket parts that have the potential to affect emissions on an engine or vehicle prior to sale in the state. Under California’s program, aftermarket after-treatment systems, such as diesel particulate filters, selective catalytic reduction systems, and catalysts, must have pre-approval by Executive Order prior to sale in California. A number of other states have followed California’s lead, creating patchwork regulation of the aftermarket parts industry.

The revised Tampering Policy presents a more unified approach at the federal level and sets forth a non-exhaustive list of six specific circumstances in which EPA may exercise enforcement discretion to determine that an entity has a “reasonable basis” that particular conduct (including the sale of manufacture of an aftermarket part) will not adversely affect emissions. A summary of each of the six circumstances is as follows:

- Reasonable Basis A: Identical to the EPA-certified configuration;

- Reasonable Basis B: Replacement after-treatment system that is as effective as the vehicle’s or engine’s original system and is durable enough to last for a period of time equal to at least half of the vehicle’s or engine’s useful life as defined in EPA regulations

- Reasonable Basis C: Addition of a new after-treatment system to decrease emissions;

- Reasonable Basis D: Emissions testing demonstrates no adverse effect on emissions;

- Reasonable Basis E: Aftermarket part certified or approved by EPA; or

- Reasonable Basis F: Aftermarket part exempted by the California Air Resources Board.

These six criteria provide additional clarity with respect to those circumstances that constitute a “reasonable basis” and provide more certainty for regulated entities. However, the policy does set forth specific considerations such as testing, recordkeeping, marketing materials, and labeling that those in the aftermarket parts industry should be aware of and implement in order to demonstrate compliance. In addition, EPA will not provide pre-approval for a “reasonable basis,” but can request that a party provide documentation to support its “reasonable basis.” The policy sets forth the types of records parties should keep to demonstrate compliance.

Status of the Catalytic Converter Policy

In addition to the Tampering Policy, EPA issued a pre-publication notice soliciting comments on its 1986 enforcement policy related to aftermarket catalytic converters/catalysts (the “Catalytic Converter Policy”). The Catalytic Converter Policy addresses the manufacture, sale, and installation of replacement catalytic converters for light-duty gasoline motor vehicles that are beyond their emissions warranty. The request for public comment has not been published in the Federal Register, but publication is expected in the near term. Once the notice has been published in the Federal Register, parties have 60 days to provide comments to EPA.

EPA is considering whether and how to update the Catalytic Converter Policy or whether to withdraw the policy in its entirety. Until EPA updates or withdraws the Catalytic Converter Policy, EPA has stated that catalytic converters for light-duty motor vehicles that are beyond their emissions warranty remain subject to the Catalytic Converter Policy. If EPA withdraws the Catalytic Converter Policy, then aftermarket catalytic converters would be subject to the general provisions of the Tampering Policy.

In the pre-publication notice, EPA broadly requests information on: (1) potential costs and air quality benefits of changing or withdrawing the Catalytic Converter Policy, (2) the current state of the catalyst market, including cost, volume, frequency of installation, age and mileage of vehicles in which these systems are installed, (3) the reason for replacement, (4) effectiveness in curbing air pollution, and (5) current industry adherence to the Catalytic Converter Policy. EPA is specifically looking for information on whether industry would prefer that EPA withdraw the Catalytic Converter Policy and rely on the Tampering Policy instead; challenges for manufacturers, distributors and retailers; and industry perspective on a reasonable timeline for transitioning away from the Catalytic Converter Policy should EPA withdraw or update the policy.

The request for information presents an important opportunity for stakeholders to review EPA’s request and provide comments to inform EPA decision-making in this area. Whether EPA withdraws or updates the Catalytic Converter Policy, catalytic converter manufacturers, retailers, and installers will need time to transition away from the current program, and to address EPA’s new enforcement position once it is final.

EPA has stated that the Tampering Policy is not a rulemaking, but rather is a nonbinding policy for EPA staff to use in exercising enforcement discretion in civil actions. Industry and parties on both sides of the aisle have generally supported EPA’s National Compliance Initiative related to tampering and defeat devices, and it is unlikely that this policy will change due to the change in administration.

For additional information on the Tampering Policy, or the status of the Catalytic Converter Policy, or for assistance in engaging with the EPA with respect to either policy, please contact Amanda Beggs or Pete Tomasi.