As we embark on the second half of 2023, Foley’s second annual Manufacturing White Paper examines the business and legal considerations that continue to impact the industry and offers the perspectives and insights of attorneys with deep experience serving as trusted advisors to manufacturing companies. Our Manufacturing Sector team continually examines the transformational shifts through the eyes of our clients and is well-positioned to help clients stay ahead of global trends and innovate in a dynamic marketplace.

Table of Contents

-

- Letter from the Co-Editors

- Everything Electrified and Connected All at Once: New Challenges Facing Supply Chains, Best Practices and Lessons Learned

- Cybersecurity Threats in the Manufacturing Industry

- The New Era of U.S. Customs Enforcement (and Compliance)

- Navigating the Domestic Content Compliance Minefield

- How to Protect Intellectual Property During Product Development

- 2023 CPSC and FDA Enforcement Trends

- Terminating Reseller Relationships Amidst the Network-Consolidation Trend: What Manufacturers Need to Know

- Top Environmental Issues Facing the Manufacturing Sector: The EPA Tackles Climate Change and Emerging Contaminants

- SEC Final Rules Mandating Compensation Clawbacks in Connection with a Restatement or Revision

- 2023 Manufacturing Sector M&A: Outlook and Tools to Maximize Strategic Transactions

- The Dawn of Generative AI in Manufacturing: Opportunities, Implications, and the Future

Letter from the Co-Editors

| AUTHORS | |||||

| Michelle Y. Ku | [email protected] | |||||

| Chase J. Brill | [email protected] | |||||

| Jonathan H. Gabriel | [email protected] | |||||

Agility and resiliency remain essential attributes for manufacturers in 2023. Manufacturers are no longer focused on figuring out when things will return to “normal.” Instead, they are applying lessons learned from the past few years to evolve their operations to succeed in this “new normal.”

Modern manufacturing and supply chains are in the midst of a sea change, as products continue a seemingly inexorable march toward electrification and greater connectedness. The movement towards electrification and connectedness presents manufacturers with both opportunities and challenges. The digital revolution in Smart Manufacturing brings complex cybersecurity risks and threats. Generative AI technologies can create new opportunities and competitive advantages for companies in the manufacturing sector, as well as risks that these companies should proactively manage to effectively deploy new AI solutions. Today’s high-tech products also require a combination of skills across an array of engineering disciplines, often resulting in necessary relationships with third parties. Avoiding disputes with these parties over intellectual property remains a key aspect of any innovation strategy.

Manufacturers are facing stiffer enforcement on a number of fronts. Manufacturers who serve as importers of record need to prioritize customs compliance, both to mitigate risks and to maintain competitive positions in the evolving trade environment. Stricter domestic content requirements present compliance challenges but also an opportunity for manufacturers who understand the rules. Manufacturers of CPSC and FDA-regulated products must diligently mitigate risk by cultivating a culture of compliance that incentivizes internal escalation of consumer reports and establish processes and procedures to assess and act on such reports in a timely manner. Manufacturers face an increasingly complex web of environmental regulations and an EPA that has demonstrated willingness to enforce them. Publicly-traded manufacturers also need to prepare now to deal with the significant implications of stock exchange rules regarding executive incentive

compensation clawbacks.

Unwinding or outright terminating reseller relationships is a regular part of business for most manufacturers when they use independent reseller networks to get their products into the hands of end users. Manufacturers should carefully consider how best to handle any reseller termination, especially in the wake of reseller consolidation or downsizing due to advancements in automation and AI.

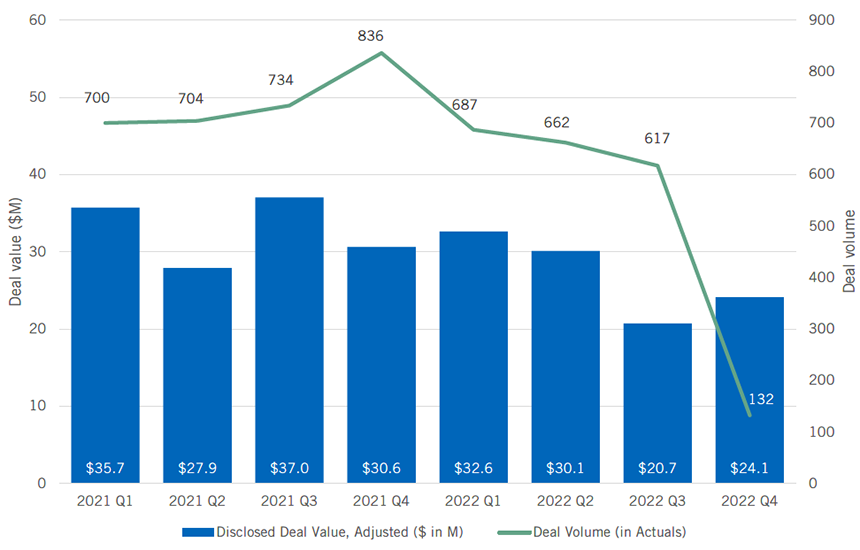

Following the historic highs of 2021, M&A activity in the manufacturing sector slowed in 2022 and remains at a cautious but stable pace in 2023. For manufacturers with strong balance sheets the current climate presents opportunities. How deals are structured will play a critical role in maximizing the results of strategic transactions.

Foley & Lardner’s Manufacturing Sector team continually examines these transformational shifts through the eyes of our clients and is well-positioned to help clients stay ahead of global trends and innovate in a dynamic marketplace.

As we embark on the second half of 2023, this Manufacturing White Paper examines the business and legal considerations that continue to impact the industry and offers the perspectives and insights of attorneys with deep experience serving as trusted advisors to manufacturing companies.

Everything Electrified and Connected All at Once: New Challenges Facing Supply Chains, Best Practices and Lessons Learned

| AUTHORS | |||||

| Vanessa L. Miller | [email protected] | |||||

| Nicholas J. Ellis | [email protected] | |||||

Modern manufacturing and supply chains are in the midst of a sea change, as products continue a seemingly inexorable march toward electrification and greater connectedness. While these two trends are common across many industries, perhaps nowhere are they more pronounced than in the automotive industry. Most major automobile manufacturers have set aggressive goals to electrify their fleets, many in the range of 40-50% by the mid-2030s. At the same time, infotainment systems and other features have grown increasingly complex (and powerful) as many manufacturers are developing components and assemblies that contain integrated software and technology. Beyond the automotive industry, even the most basic household appliances are now wireless and connected. We have long since passed the point at which a basic automobile surpassed the computing power of a NASA space shuttle. It is (perhaps) only a slight exaggeration to suggest we may see a day in the not-too-distant future when our coffee makers do so as well.

The movement toward electrification and connectedness presents manufacturers with both opportunities and challenges. Those who take advantage of these opportunities and adapt to the changing landscape will thrive. Those who do not will see their market shares diminished and, ultimately many may not survive.

Opportunities: Innovation and Reinvention

Significant changes in manufacturing and supply chains present a new competitive landscape and opportunities for manufacturing companies. With these changes comes the need for new technologies. New technologies bring new players, including new companies. Some of these new companies are truly “new” in the literal meaning of the word. They are startups created to monetize new technologies and products. Other “new” companies that may present opportunities may have been around for some time, they can be considered “new” to a particular field or industry such as legacy automotive manufacturers as they expand their traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) offerings to include more electric vehicles and incorporate autonomous and other connected technologies. Both startups and legacy companies represent potential new business opportunities and relationships for manufacturing companies.

New technologies and new customers present a growing demand for new products or components and require supplier capacity to manufacture those products or components for the market. There also is a need for new and innovative solutions to meet the demands of these changing technologies. These opportunities may be even more attractive because, in many of these new fields, there is less status quo or established market players, which can make breaking into the field less of a challenge for new participants. All of this adds up to significantly more opportunities for companies that are able to seize the initiative.

Challenges: The Risks Surrounding Novelty

While change brings many opportunities, it also brings challenges, including new technologies, new companies, and new relationships. No, that is not a mistake; these are indeed the same things that we listed in the previous section as opportunities. While “new” presents many opportunities, the flipside of those same opportunities are the elements of risk.

In the case of new technologies, there always will be some degree of working out the kinks, both with respect to performance and durability. The most obvious way in which these risks can manifest is through warranty claims and customer complaints. However, they can present other risks as well. For example, a supplier may make significant investments in production capacity for a customer bringing a new product to market. However, if the customer is unable to fully validate the product and launch is delayed or volumes reduced, the supplier can be left with unrecovered investments. The fact that many of these risks are unknown and lack historical data or precedent can make it more difficult for companies to price these risks into their cost walks when quoting new business.

Dealing with new companies in an industry (as either a supplier or a customer) brings its own set of challenges. New companies often have a limited track record or, in the case of legacy companies expanding into new fields, a limited track record within that particular field. They may also have a different worldview that can cause friction, or at least miscommunications and misaligned expectations between different companies. Perhaps the most commonly cited—although at times overstated—examples of such differing cultures coming together is the difference in cultures between traditional automotive manufacturers and companies in Silicon Valley. New companies may have limited resources and expertise necessary to overcome hurdles that may arise. Particularly in the case of startups or other new ventures, there may also be questions about whether new companies have the financial resources to meet their contractual obligations, should challenges arise.

All of these risks can be further compounded when they occur in a new relationship with a new customer or supplier. Unlike many well-established relationships (assuming they have been good relationships), newer relationships do not have the track record of trust and historical understanding on which to fall back when things get difficult. New business partners are more likely to question the motives, sincerity, or even ability of the other side, and can be more likely to reach for legal remedies should problems arise in the relationship.

Strategies and Best Practices

While the movement toward electrification and connectedness in the automotive and other industries can present challenges, there are a number of strategies and best practices that companies can employ to mitigate the risks these challenges pose.

- Consider your approach to software and integrated technology. Whether your company will develop, license, or own a particular software or integrated technology will be a major strategic driver. The key question that many manufacturers will face is “to build or to buy?” Each path comes with its own list of pros and cons that need to be carefully considered in the context of the companies’ abilities, particular product, related costs and marketplace leverage.

- Strong contracts to protect against risks posed by new technology and new business partners. In a changing world, one of the most important steps that companies can take to protect themselves largely remains the same – protecting themselves through their contracts. Companies entering into a new supply relationship should give careful consideration to the key terms of the arrangement, including at least the following: (i) quantity, (ii) term/termination, (iii) price (including price adjustment), (iv) warranties, (v) indemnification, (vi) intellectual property, (vii) choice of law/forum, and (viii) force majeure. For example, companies that are concerned about the performance of a new supplier’s technology should ensure that any purchase contract includes strong warranties and other assurances of performance. Companies that may be concerned about the viability or performance of a supplier should consider seeking licenses or other rights that would enable to obtain vital components from another source if the supplier does not meet its obligations. This directive is not limited to supply contracts alone. Any contract into which a company is entering to take advantage of the opportunities presented by these changes should be carefully considered and calibrated for the risks presented by that particular opportunity.

- Consider the form of the relationship to mitigate potential risks. At the outset, companies can mitigate a significant amount of their potential risks and maximize opportunities by properly considering what form the relationship should take. For example, does it make sense to enter into a traditional customer supplier relationship? In some cases the answer may be yes; however, this is not always the case. For example, if a potential new supplier has developed a technology that your company wants to take advantage of but has no track record of production or manufacturing facilities, it may be more appropriate to consider an alternative structure such as a licensing agreement or some form of joint venture. Larger customers that want to ensure long-term access to technology may prefer to protect that investment through some form of investment, or even outright purchase of a provider rather than through a supply agreement alone.

- Due diligence, including promised technology and IP rights. It should go without saying, but companies can avoid many headaches (or at least fully understand what they are getting into) by properly vetting their prospective business partners. Key issues to consider include looking at the technological, financial, and operational resources of a prospective business partner to ensure that they are able to perform their obligations, but also looking at their reputation and track record. For example, a litigation search can be very telling. If a company has been in business long enough, it is inevitable that a company will have some kind of litigation history. However, certain issues can present significant red flags. For example, if a company is facing litigation challenging its intellectual property rights or alleging infringement, this may present a significant risk as to whether the company has viable rights to the technology it is offering. Other examples require little or no explanation – if a company has been sued by multiple suppliers in the last month for nonpayment, it probably does not present a good opportunity as a new customer. Finally, appropriate diligence should be performed on any new or unproven technology being offered, with a view to the “golden rule” – if it sounds too good to be true, it very well might be.

Adapting to a Changing Landscape

Unfortunately for some companies, creation and progress often involve a measure of destruction. Changing technology inevitably will leave some companies behind. In few places are these risks more evident than in the automotive industry as the shift to electrification in particular represents a fundamental change to the demands placed on the automotive supply chain. There undoubtably will be challenges along the way and it may take longer than the currently expected 10-15 years, but the path is largely locked in as most automotive manufacturers and their supply base are committing to investments in electrification. For companies that primarily manufacture products that are used only in traditional internal combustion engine vehicles – for example, fuel tanks – this presents a clear and obvious problem. How many companies can survive a 40-50% decline in their business?

Unfortunately for some companies, creation and progress often involve a measure of destruction. Changing technology inevitably will leave some companies behind. In few places are these risks more evident than in the automotive industry as the shift to electrification in particular represents a fundamental change to the demands placed on the automotive supply chain. There undoubtably will be challenges along the way and it may take longer than the currently expected 10-15 years, but the path is largely locked in as most automotive manufacturers and their supply base are committing to investments in electrification. For companies that primarily manufacture products that are used only in traditional internal combustion engine vehicles – for example, fuel tanks – this presents a clear and obvious problem. How many companies can survive a 40-50% decline in their business?

Companies facing these changes need to consider carefully what their future looks like in the medium- to long-term horizon and develop a plan for how they will adapt. Key factors to consider include such considerations as:

- What does your company’s product mix look like now, and how will those products be affected by impending changes in the industry?

- What new products are going to be needed as a result of these changes?

- How are software or new technologies integrated with your products (or how can they be integrated)?

- Who are your customers?

- Where do you need to be located geographically?

- How about your supply base and their geographic locations?

- What is the appropriate structure for a strategic partnership with a particular customer or supplier?

Once a company has assessed its risks and developed a plan to address those risks, it can move forward with making the necessary investments and changes to its business. If you haven’t started, you are already behind!

Cybersecurity Threats in the Manufacturing Industry

| AUTHORS | |||||

| Aaron K. Tantleff | [email protected] | |||||

| Alexander Misakian | [email protected] | |||||

In the hyper-connected era of Smart Manufacturing, accelerated by “Industry 4.0,” manufacturing is undergoing a digital revolution. By leveraging technologies such as advanced automation, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, blockchain, and other technologies, manufacturers continue to optimize production, increase efficiency, and drive innovation. However, this digital revolution brings complex cybersecurity risks and threats, creating significant implications for manufacturers.

For the second year in a row, manufacturing has been the most targeted sector by cyberattacks, accounting for nearly one in four incidents.1 Throughout 2022 alone, ransomware attacks on the manufacturing industry nearly doubled, accounting for 72% of all ransomware attacks and implicating 104 unique manufacturing subsectors.2

As manufacturers increasingly integrate digital information technology with physical operational technology, the vulnerabilities that cybercriminals can exploit continue to multiply exponentially. Accordingly, while cybersecurity has always been an essential aspect of manufacturing, the increasing reliance on technology now makes cybersecurity one of the industry’s most critical concerns. Below, we describe various types of cybersecurity risks and attacks faced by manufacturers and outline some of the legal implications and considerations that entities in the manufacturing industry should consider.

Types of Cybersecurity Risks Facing the Manufacturing Sector

Cybercriminals continue to target the manufacturing sector due to its integral role in the economy, potential critical industry and supply chain impacts, and vast amounts of sensitive data held by organizations within the sector. Cyberattacks may disrupt businesses and supply chains, undermining the benefits of digitalization and resulting in financial and productivity losses causing reputational damages.

These cybersecurity risks can be broadly categorized into malware attacks, social engineering attacks, and Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs), in addition to other risks unique to the manufacturing sector.

Malware Attacks involving the deployment of malicious software, may come in many forms, including viruses, worms, ransomware, and spyware, and constitute a significant threat to manufacturers as they can cripple an entire manufacturing operation, causing significant financial, operational, and reputational damage. This category of software is designed to infiltrate, damage, or disrupt systems. The most common malware affecting manufacturing is ransomware, which may involve the encryption and/or exfiltration of a victim’s data and a ransom payment demand. Ransomware is especially dangerous for a manufacturer as it can halt production lines, disrupt operations, cause considerable financial loss, and significantly impact the global supply chain.

Social Engineering Attacks exploit human vulnerabilities rather than technological flaws to gain unauthorized access to systems and data, potentially leading to ransomware attacks or sensitive data theft. While phishing is a well-known form, social engineering attacks may involve spear-phishing (targeted at specific individuals or companies), baiting (enticing a user to perform an action with a false promise such as a free gift), and pretexting (creating a fabricated scenario to manipulate the victim into providing access or information).

Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) are sophisticated, coordinated attacks that often target high-value industries like manufacturing. These attacks are typically conducted by highly skilled groups with substantial resources, intent on stealing sensitive information or disrupting critical infrastructure. In the manufacturing sector, APTs often target valuable intellectual property (IP), such as proprietary production techniques, research and development data, or business strategy documents. In addition to intellectual property theft, APTs can cause significant operational disruption as prolonged, unauthorized access to a manufacturer’s network may allow attackers to manipulate industrial control systems, disrupt production processes, or even sabotage equipment. APTs can also compromise supply chains. A successful attack on a manufacturer could give the attacker access to connected networks, such as suppliers, logistics partners, or customers. This potential for wide-ranging impact makes APTs a grave concern for the entire manufacturing ecosystem.

Intellectual Property Theft is one of the most coveted manufacturing targets for cybercriminals. Manufacturers often possess valuable proprietary information, including blueprints, manufacturing processes, research, and development data. Accordingly, sophisticated cybercriminal groups or state-sponsored entities may utilize APTs, among other cyber-attack tools, to target and exfiltrate IP. Given the value of proprietary information such as unique manufacturing methods, product designs, and research data, the impact of such theft on a manufacturing company can be immense, leading to potential market share loss, decreased competitive advantage, and substantial financial repercussions.

Supply Chain Attacks, often resulting from APTs, exploit the vulnerabilities in a company’s supply chain network. Given the interconnected nature of the manufacturing industry, a single vulnerability can have far-reaching implications. Attackers can exploit weaker links, such as small suppliers with less robust security, to infiltrate larger, more secure networks. Notably, the 2020 SolarWinds hack, which affected government and corporate networks, was a supply chain attack.

Industrial Control System (ICS) Attacks, also often stemming from APTs, target industrial control systems crucial for modern manufacturing processes and can potentially give the attacker control over production processes. Such an attack can halt production, cause physical damage, or even result in safety incidents. Stuxnet, a malicious computer worm discovered in 2010, targeted ICS in Iran’s nuclear facilities, highlighting the potential real-world implications of such attacks.

Insider Threats from disgruntled employees, contractors, or other insiders with access to critical systems can prove just as dangerous cybersecurity risks as threats from outside the organization. As with other types of cyber threats, insider threats pose a significant risk of IP theft. Notably, not all insider threats are intentional. While insiders might misuse their access intentionally, their credentials can also be co-opted through phishing or other methods, allowing an external attacker to infiltrate systems.

Third-Party Vulnerabilities involve cybersecurity risks that result from a manufacturer’s relationships with vendors, suppliers, service providers, or any third parties that have access to their systems or data. In other words, a manufacturer’s cybersecurity resilience is often only as strong as the weakest link in its supply chain. A third party lacking robust cybersecurity measures can become an initial vector for cybersecurity attacks.

Potential Impact on Critical Infrastructure

The manufacturing sector often serves as a backbone to critical infrastructure – the systems, facilities, and essential services that underpin the functioning of our societies and economies. This encompasses sectors such as power generation, water supply, transportation, telecommunications, and healthcare. Manufacturers play an instrumental role in supporting these infrastructures by providing essential components, equipment, and services necessary for their operation. Consequently, a cyberattack that significantly disrupts manufacturing processes can have wide-reaching and potentially catastrophic impacts on critical infrastructure, the economy, and national security.

Energy. A cyberattack on manufacturers in the energy sector, including those that provide parts for power plants, oil refineries, and wind turbines, could result in widespread power outages, leaving homes, businesses, and public services without electricity. This could affect thousands, if not millions, of individuals and cause significant economic damage. At an extreme, it could even have national security implications, as energy grids could be left vulnerable to additional attacks.

Transportation. Similarly, in the transportation sector, a successful cyberattack on manufacturers of automobile, aircraft, and train components could disrupt the availability of these parts and impact production. The cascading effect of such disruptions could lead to decreased transportation capabilities, major disruptions to the supply chain, and the availability of vehicles or goods, significantly impacting the mobility of goods and people and potentially even impacting military readiness if defense-related transportation is affected.

Telecommunications. In telecommunications, manufacturers produce everything from networking equipment to mobile devices. A disruption in manufacturing these products could have a ripple effect, causing communication blackouts that affect businesses, government agencies, and individuals. Such an event could severely disrupt daily operations across multiple sectors and hinder emergency response efforts.

Healthcare and Pharmaceuticals. When it comes to healthcare and pharmaceuticals, cyberattacks can have particularly dire consequences. For example, an attack on medical device or pharmaceutical manufacturers could result in medication production shutdowns, compromised medical device functionality, or altering the formulation of life-saving drugs. In the worst-case scenario, this could have severe repercussions on patient safety and public health.

National Security. Cybersecurity attacks on any of the critical infrastructure sectors noted above may have major national security implications, particularly if the targeted manufacturing company is involved in producing defense equipment or technology. A cyberattack on manufacturers supplying the defense sector could interrupt the production of essential military equipment, impairing a nation’s defense capabilities, or result in our nation’s enemies gaining access to the IP underlying critical defense technology. Similarly, disruptions in the energy or telecommunications sectors could compromise key national capabilities and intelligence operations.

Overall, the potential impact of cyberattacks on critical infrastructure underscores the urgent need for robust cybersecurity measures within the manufacturing sector. The interconnectedness of today’s world means that a cyberattack on a single manufacturing company can ripple outwards to affect a broad array of unrelated sectors. Moreover, these attacks can undermine the public’s trust in critical services, causing societal instability. Given the

potential scale of disruption and associated economic, health, safety, and national security risks, manufacturers must adopt a proactive approach to cybersecurity. Cybersecurity in the manufacturing sector is not merely an issue of business continuity, it is a matter of national and international security.

Legal Implications and Potential Liabilities

The legal implications of these cybersecurity attacks are vast, including significant financial and legal liabilities from various sources. First, manufacturers may face liability based on data protection laws if a cybersecurity attack involves a personal data breach. For example, if a manufacturing company controls large amounts of personal data, including customer or employee data, it would be subject to data protection laws such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union and the California Privacy Right Act (CPRA) in the United States. A data breach that exposes or results from noncompliance with data protection laws could result in significant regulatory fines and penalties. For instance, the GDPR imposes significant financial penalties for noncompliance, up to 4% of annual global turnover or €20 million, whichever is higher. Additionally, manufacturers may face considerable liability arising from class actions filed by affected individuals.

Second, directors and officers of manufacturing companies could face legal action from shareholders based on an alleged breach of fiduciary duties. Such duties include the duty of care, which could be interpreted as an obligation to implement reasonable cybersecurity measures in the context of cybersecurity. If a cybersecurity attack results in significant financial loss and the shareholders can show that directors and officers failed to implement adequate cybersecurity measures, they could be held liable for breaching the duty of care. Similarly, if a cybersecurity attack results from a failure to properly vet and monitor a supplier or other third party’s cybersecurity policies and procedures, manufacturers may face potential claims alleging a breach of the required duty of care. Shareholders may also file lawsuits alleging that negligence of the directors and officers resulted in financial loss.

Third, if a cybersecurity attack involves the loss or disclosure of IP, especially in the case of industrial espionage, a company may be found to be in violation of trade secret laws or be subject to IP lawsuits if the cybersecurity attack results in the theft and subsequent disclosure and/or unauthorized use of proprietary information.

Finally, under contract law, manufacturers could be held liable for breach of contract if a cybersecurity attack disrupts their ability to fulfill contractual obligations. Additionally, contracts often contain clauses related to required data protection and cybersecurity. This could lead to various legal consequences, including termination of contracts and liability for any resulting damages.

Recommendations for Manufacturers to Manage Cybersecurity Risks

Given the multitude of cybersecurity risks and significant legal implications, manufacturers must adopt and comply with robust cybersecurity measures and policies, including technical and legal measures.

Technical Measures. These include implementing multi-factor authentication, utilizing modern endpoint detection solutions, ensuring comprehensive business continuity and backup procedures, regularly updating and patching systems, conducting regular security audits, and training employees on cybersecurity best practices. Technical measures are the first line of defense against cybersecurity risks. Manufacturers should review their cybersecurity policies and procedures, and ensure proper technical security measures are implemented and followed.

Employee Training and Awareness. Employees often represent the most significant, and most difficult to manage, vulnerability in an organization’s cybersecurity defenses. As such, regular employee training and awareness campaigns are crucial. Training should educate employees about the nature of cyber threats, the importance of cybersecurity measures, and their role in defending against them. Topics can include the importance of strong, unique passwords, the risks of phishing attacks, and the correct procedures for handling, storing, and sharing sensitive data.

Legal Measures. Manufacturers can also protect themselves by incorporating appropriate and compliant cybersecurity clauses into their contracts. For example, to mitigate the risks associated with third-party vulnerabilities, these clauses should specify third parties’ responsibilities regarding cybersecurity, including data protection obligations, required security measures, and the procedure for responding to cybersecurity incidents. Manufacturers should also ensure they conduct thorough cybersecurity audits of their third parties. These audits should assess the third parties’ cybersecurity policies, procedures, infrastructure, and compliance with relevant regulations. These clauses and audits protect manufacturers legally and incentivize third parties to uphold high cybersecurity standards and limit liability in the event of a cybersecurity attack.

Cyber Insurance. Manufacturers also should invest in cyber insurance to mitigate financial risks associated with cybersecurity attacks, including the costs to investigate, remediate, and respond to such attacks, negotiations and ransom payments, and potential litigation that may arise. Additionally, manufacturers should strive to comply with applicable cybersecurity standards such as ISO 27001 and the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, as these standards provide guidelines and best practices for managing cybersecurity risks. Achieving and maintaining these certifications can demonstrate that the company has taken reasonable steps to protect against cybersecurity threats.

Consider Collaborating with Legal Counsel

Manufacturers face not only a multitude of cybersecurity risks but must also navigate the complex patchwork of cybersecurity and data privacy laws at the state, federal, international, and industry-specific levels. These often complicated laws can vary widely depending on the jurisdiction, industry, and the type of data a company handles. Legal counsel can identify the applicability and ensure compliance with laws like the GDPR, CPRA, and other comprehensive data privacy laws, including cybersecurity requirements imposed by the federal government under the Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act of 2022 (CIRCIA), the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), and other industry-specific regulations.

Legal counsel also can help identify potential liabilities and legal risks related to cybersecurity. This may include facilitating risk assessments, developing risk management strategies, including policies and procedures to mitigate cybersecurity risks, and preparing and executing an appropriate incident response plan following a cybersecurity incident to ensure compliance with applicable data breach privacy laws. Legal counsel can also assist in reviewing and revising contracts with suppliers, service providers, and customers to ensure the inclusion of appropriate cybersecurity requirements and protections, such as indemnification clauses or limitations of liability in the event of a cybersecurity incident. Finally, legal counsel involved and well-versed in a manufacturer’s cybersecurity practices and procedures can more effectively assist in the event of litigation, whether from affected individuals, business partners, or regulators.

Managing cybersecurity risks requires a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach combining robust technical measures, strong legal protections, and a commitment to employee training and awareness. By implementing these measures, manufacturers can significantly reduce their cybersecurity risks and protect themselves from potential legal liabilities.

Conclusion

While offering significant advantages, the digital revolution in the manufacturing industry has exposed the sector to elevated cybersecurity risks. As cyber threats grow more sophisticated, manufacturers must navigate a complex legal landscape, balancing technologically supported growth with compliance with data protection laws, potential liability for cyber breaches, and the need for robust cyber defenses.

In this rapidly evolving context, proactive risk management and adherence to cybersecurity standards are not merely best practices but strategic imperatives. Manufacturers should continually revisit their cybersecurity strategies, aligning them with the latest technological advancements and regulatory updates. Fostering a strong cybersecurity culture will not only mitigate legal liabilities but will also contribute to the long-term resilience and competitiveness of the manufacturing sector.

——————————————————–

1 See “X-Force Threat Intelligence Index 2023,” IBM Security, February 2023.

2 See “ICS/OT Cybersecurity Year In Review 2022,” Dragos.

The New Era of U.S. Customs Enforcement (and Compliance)

| AUTHORS | |||||

| Gregory Husisian | [email protected] | |||||

| John E. Turlais | [email protected] | |||||

In recent years, the United States has experienced a notable shift in trade policies, marked by an increase in high-rate special tariffs and intensified enforcement measures implemented by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). These developments have significantly impacted the international trade for manufacturers. With the U.S. government using as a tool to protect domestic industries, promote fair trade practices, and address perceived imbalances with China, manufacturers who serve as importers of record need to prioritize customs compliance, both to mitigate risks and to maintain competitive positions in the evolving trade environment.

Customs Compliance Is Essential in the Current Enforcement Environment

Recent developments that have made customs a critical compliance area include:

- Unprecedented implementation of high special tariffs, including 10 and 25 percent Section 232 duties on aluminum and steel, Section 301 tariffs of up to 25 percent on nearly all goods from China, and a record number of antidumping and countervailing duty cases, which can impose tariffs into the triple digits.

- CBP’s renewed emphasis on enforcement and revenue collection, given the much greater tariffs that it is now collecting.

- The long-awaited completion and full implementation of the Automated Commercial Environment (ACE) portal, which gives CBP the tools to run sophisticated searches to find anomalies in import patterns, including misclassifications, undervaluation of entered value, and erroneous country-of-origin declarations that can lead to large underpayments of customs duties.

- The New Enforcement priorities and increased budgets particularly with respect to forced labor issues, such as the requirements imposed under the Uyghur Forced Labor Act

- Increased use of electronic portals, such as the e-Allegations Program and the Enforce and Protect Act (EAPA) Program, by which members of the trade community can report suspected trade violations to CBP.

These developments signal a new paradigm of increased CBP enforcement. Notably, the change in presidential administrations did not result in any material changes to the U.S. international trade policy. There continues to be bipartisan support to keep pressure on China (via high tariffs and AD/CVD orders) to deal with perceived Chinese government manipulation of the international trade, investment, and intellectual property norms. Other important developments, such as the migration to the ACE portal and the ability to report potential violations more easily online, are permanent fixtures.

Manufacturers that act as importers of record accordingly must remain vigilant in customs matters, including by implementing rigorous and consistent customs compliance procedures, such as those outlined below.

Customs Compliance Best Practices

Our recommendations for customs compliance are based on the expectations of CBP and long-standing work with importers. Some key items we recommend include the following:

- Start by Recognizing Your Company Is Ultimately Responsible. CBP regulations place the burden for accuracy in the importation and payment of duties on the importer of record – not the broker or freight forwarder, as some importers mistakenly believe. The importer of record is responsible for, among other things, accurately determining the country of origin, correctly classifying the goods, determining if any extraordinary duties are due, complying with all free-trade agreement requirements, ensuring goods are not a product of forced labor, and fully paying all tariffs. In the case of errors, standard broker agreements generally limit recovery to the nominal fees associated with each entry, while the importer of record remains fully responsible for all underpayments and associated penalties.

- Prepare a Customs Compliance Manual. Based on our experience in recent audits, CBP expects importers to go beyond a simple compliance policy and instead implement a comprehensive customs compliance program with a manual that includes written procedures and internal controls for each of the relevant elements of reasonable care. Importers that memorialize such measures in a customs manual tailored to its operations are less likely to have import-related errors and are in a better position to explain the scope and implementation of customs compliance programs to CBP auditors.

- Create a Customs Classification Index. We recommend importers regularly review the products they import and confirm the accuracy of the associated HTS tariff classification codes. The U.S. government updates these codes periodically throughout the year, and new products may need new classifications. Importers should maintain the most current HTS classifications in a database that is available to their third-party customs brokers or other parties responsible for preparing customs entry filings.

- Review Product Valuations & Declared Value. Importers should review the methodologies used to calculate the ad valorem value of the products they import, paying particular attention to transactions involving related or affiliated companies. Notably, transfer pricing requirements under CBP regulations differ appreciably from transfer pricing requirements imposed by the IRS, thus often requiring manufacturers to prepare a customs-specific transfer pricing analysis Special attention is also necessary to determine whether the valuation includes all relevant off-invoice items, such as royalties and assists.

- Coordinate with Customs Brokers & Freight Forwarders. Importers should engage with their freight forwarders and customs brokers to determine whether they are consistently following CBP requirements and should coordinate regarding required customs recordkeeping. These areas should not be left to customs brokers on their own because, as noted above, CBP will ultimately hold the importer of record responsible for any compliance lapses.

- Conduct an Internal Customs Compliance Audit. Importers who are at a heightened risk for a customs inquiry or scrutiny, such as companies that frequently import goods from China or goods subject to potential antidumping or countervailing duties, should consider performing an internal customs audit to determine whether existing compliance systems are effective. A good starting point for such an audit may be found in the questionnaire at the end of CBP’s Importer Self-Assessment Pilot Program publication.

- Conduct Compliance Training. Importers should train relevant employees on CBP requirements annually. Such employees typically include customs compliance staff, procurement personnel, and individuals working in the company’s shipping/ logistics departments. Relevant compliance topics include:

- Importer of record responsibilities;

- Classifying imported goods;

- Determining countries of origin;

- Making preferential tariff claims under the USMC and other FTAs;

- Coordinating with customs brokers and freight forwarders;

- Conducting post-entry checks and making corrections;

- Tracking assists and other valuation issues; – related party pricing considerations;

- Identifying and claiming relevant section 301 exclusions; and

- Recordkeeping responsibilities.

- Evaluate USMCA/FTA Claims. Importers should review their use of FTA or other tariff duty preference programs to determine whether they are applying the eligibility criteria properly and have the documentation necessary to support their claims. If the goods come from Canada or Mexico, then claims for preferential tariff treatments should be evaluated against the USMCA rules, which often differ from the older NAFTA requirements. Some of the key issues to consider include:

- Whether the imported goods meet USMC’s regional content requirements;

- Whether required certificates of origin are available at the time of entry (with appropriate blanket periods identified); and

- Whether the company maintains all of the required documentation to support free-trade preferences for the appropriate period of time.

- Review Products for Antidumping and Countervailing Duties. Finally, companies should periodically review their imported goods to determine whether they may be subject to additional tariffs under various antidumping or countervailing duty orders.

Dealing with CBP Requests for Information: Informed Compliance Letters and Form 28s/29s

A relatively recent development is the issuance of “informed compliance” letters by CBP, a tactic we expect CBP will continue to use more in the future. These letters often are issued to major U.S. importers to encourage them to review their recent entries and determine if they have treated entries correctly where they acted as the importer of record. These letters often are sent to major importers who have not been audited in the past decade or that are viewed as being at a higher risk for violations. At the same time, CBP is sending out an increasing number of Forms 28s (requests for information) and Form 29s (notices of action), which CBP expects importers will broadly apply to all similar imports.

A relatively recent development is the issuance of “informed compliance” letters by CBP, a tactic we expect CBP will continue to use more in the future. These letters often are issued to major U.S. importers to encourage them to review their recent entries and determine if they have treated entries correctly where they acted as the importer of record. These letters often are sent to major importers who have not been audited in the past decade or that are viewed as being at a higher risk for violations. At the same time, CBP is sending out an increasing number of Forms 28s (requests for information) and Form 29s (notices of action), which CBP expects importers will broadly apply to all similar imports.

The receipt of these types of communications means CBP has reviewed the data of an importer of record and likely identified specific problems with its import transactions, putting the company at an increased risk of a comprehensive audit. According to CBP officials for informed compliance letters, the expectation is that companies that receive these letters will soon be the subject of a “focused assessment” or other type of CBP audit in the near future. The letters thus are a way of encouraging major importers to enhance their compliance and file voluntary self-disclosures in anticipation of the audit. To provide further “encouragement,” CBP has indicated that companies that do not follow up with a voluntary self-disclosure can expect any subsequently discovered violations will be subject to higher-than-normal penalties. The letters warn not only of potential monetary penalties, but also the prospect of seizure or forfeiture of imported merchandise.

Best practices when receiving these types of communications from Customs include:

- Determining the scope of impacted entries;

- Preparing for a potential CBP audit;

- Reviewing customs compliance policies;

- Reviewing the care taken by its customs brokers;

- Conducting a risk assessment, including regarding the issues identified in the letter or Form 28s/29s;

- Determining if HTS classifications are correct and supported by the product attributes;

- Determining whether any post-entry adjustments are needed;

- Determining whether free trade preferences are supported by FTA certificates of origin and appropriate regional content;

- Evaluating whether off-invoice items such as royalties and assists are appropriately recognized; and

- Considering whether there are any other issues in the company’s import data to indicate compliance failures and penalty risks.

While the assessment should start with the issues identified in the letter, the review should be comprehensive. Further, the review also should cover the rigor of the importer’s compliance measures and training, as these are evaluated by CBP in an audit. Any errors should be documented, and a plan put in place to strengthen the company’s compliance procedures and internal controls to prevent their recurrence.

Voluntary Disclosure

If potential violations are discovered, the importer also should strongly consider filing a voluntary disclosure. This can be accomplished using an initial marker letter, which informs CBP that an investigation of potential compliance lapses is ongoing. The marker letter then is followed by a complete disclosure, (60 days by regulation), although it is possible to request a longer time period or later to request extensions.

Voluntary disclosure of violations to CBP – if done before CBP initiates a formal investigation of potential violations – can provide numerous significant benefits to importers of record. Most notably, voluntary disclosure often results in back payment of duties and interest owed, but no penalties, if the mistakes were the result of negligence. And, even in cases of gross negligence or fraud, voluntary disclosure can result in significant mitigation of penalties and enforcement actions if the disclosure is made in good faith and includes all relevant information.

Voluntary disclosure allows importers to take control of the investigation process. By promptly identifying and reporting violations, importers can proactively address the violations, implement corrective measures, and prevent similar violations from occurring in the future. This proactive stance can help importers avoid full CBP audits, as well as protect their reputation, maintain business continuity, and avoid potential disruptions to their supply chains.

Finally, voluntary disclosure can serve as a valuable tool for understanding CBP regulations and memorializing/ improving compliance best practices. This knowledge, in turn, will help mitigate future violations and – as we have found in a number of voluntary disclosures in which we have been involved – could lead the importer to discover tariff-saving opportunities that were missed in prior years.

Navigating the Domestic Content Compliance Minefield

| AUTHORS | |||||

| Frank S. Murray Jr | [email protected] | |||||

“Buy American” requirements in U.S. federal contracts date back nearly 100 years, to the Great Depression, but the policy of trying to ensure federal dollars are spent on U.S.-manufactured products has never been more pervasive than it is today. Recent legislation authorizing new federal spending or creating new multibillion-dollar programs has made compliance with stricter domestic content requirements a precondition to the receipt of federal funds. It is safe to say that “Buy American” or “Buy America” requirements—and, as will be discussed below, there is a difference—are having their proverbial moment.

While some federal agencies have historically applied certain “Buy America” requirements to their infrastructure programs, a portion of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for the first time required all federal agencies to impose domestic content requirements on infrastructure programs receiving federal financial assistance. The so-called “Build America, Buy America” Act—referred to as “BABA” for short—created a new set of domestic manufacturing and content requirements for manufactured products, iron and steel products, and construction materials that are continuing to be implemented through agency-specific guidance and waivers.

Manufacturers face several challenges in complying with these domestic content requirements, not the least of which is understanding what set of requirements applies to a particular product or a specific project. There is a common misconception that there is a single set of “Buy American” requirements, but the truth is that domestic content requirements can vary depending on the project, the product, or even how a product will be used on a specific project. Many projects require manufacturers to submit certifications of their products’ compliance with the applicable domestic content

Despite these challenges, these domestic content requirements also present an opportunity for manufacturers who understand the rules and have taken the steps necessary to ensure their sourcing and manufacturing processes pass muster under them. This article discusses some key strategies for assessing compliance with domestic content requirements.

Know What Domestic Content Rules Apply to the Project

It may seem self-evident to state that you need to know what the rules are to be able to ensure you comply with them, but that principle is especially salient in the realm of domestic content requirements. There are different regimes that apply to direct federal procurements of construction materials or supplies—such as a purchase by the U.S. Department of Defense—and to projects overseen by state or local government entities that have received federal financial assistance. Direct federal procurements are subject to the Buy American Act (“Buy American”), while projects receiving federal financial assistance are subject to a “Buy America” requirement, such as BABA. While there are some similarities between the two regimes, there are some important differences between “Buy American” and “Buy America” requirements.

Buy American. One significant difference is that Buy American Act contract clauses provide more flexibility for suppliers of commercially available off-the-shelf, or “COTS,” items. A COTS item is a product that is sold in substantial quantities in the commercial marketplace and is offered to the government without modification from the manner in which it is sold commercially. Under the Buy American Act, a COTS item is considered domestic so long as it is manufactured in the United States, without regard to the country of origin of the components of that COTS item. In other words, there is no cost-of-components test required for a COTS item under the Buy American Act.

If the value of the contract exceeds certain dollar thresholds—generally, $183,000 for purchases of supplies, and $7,032,000 for construction projects1— the Buy American Act requirements can be waived for products of countries with which the U.S. government has entered trade agreements. When this so-called “Trade Agreements Act” provision applies, the product of a trade agreement country is treated the same as a domestic product and can be supplied on the project without a waiver. This can provide the opportunity to supply products that are not manufactured in the United States, provided they are manufactured in a country identified in the relevant contract clause as one subject to a bilateral or multilateral trade agreement to which the United States is a party.

Buy America. The “Buy America” requirements imposed by BABA are, in certain key respects, more onerous than those imposed under the Buy American Act for direct federal procurements. For example, a manufactured product—even a COTS item—is not considered “domestic” under BABA unless it meets two tests: (1) it is manufactured in the United States, and (2) its domestic-origin components account for more than 55% of the cost of all its components (the so-called “cost-of-components” test). The application of the cost-of-components test can be particularly tricky for manufacturers who are not familiar with the test and have not had occasion to assess the countries of origin of their products’ components.

It is also far less likely that a manufacturer can use a product of a trade agreement country on a BABA project, because that would require the state or local government entity that is administering the project to be covered by the trade agreement. While there may be some state government entities that are covered by the World Trade Organization’s Government Procurement Agreement, in practice very few state or local agencies receiving federal financial assistance on an infrastructure project will be subject to a trade agreement.

BABA Agency-Specific Implementation. Even under the umbrella of BABA, there can be variations in how the general requirements are implemented on specific projects. That is because each agency is responsible for implementing the BABA requirements, or a similar Buy America requirement, in the projects that it administers and funds. While there is overarching guidance provided by a central U.S. government entity—the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)—agencies can and have adopted their own waivers of the BABA requirements and, in some cases, have defined terms that remain undefined in the OMB guidance. Moreover, U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) agencies that had their own longstanding “Buy America” rules prior to BABA have generally continued to apply their existing “Buy America” requirements, sometimes with slight modifications to address new wrinkles added by BABA, such as the coverage of non-ferrous “construction materials.”

Thus, knowing what federal agency is involved in overseeing a project subject to a BABA or “Buy America” requirement is critical to understanding the specific parameters of that requirement and what, if any, exceptions or waivers may apply.

Know What Domestic Content Rules Apply to Your Product

Once you have identified the relevant set of Buy American or Buy America rules governing a specific project, another critical aspect of compliance is figuring out how the product you manufacture fits into those requirements. One critical element is determining whether your product would be considered a “manufactured product” or would be subject to the special iron/steel sourcing rules for a predominantly iron or steel product. In the BABA context, non-ferrous construction materials are subject to their own set of sourcing and domestic manufacturing requirements. Knowing whether your product—or the product into which your product will be installed—will be treated as a manufactured product, iron or steel product, or non-ferrous construction material establishes the domestic manufacturing/sourcing standard to which your product will be held.

This exercise also requires an understanding of how your product fits into the supply chain for the project subject to a Buy American or Buy America requirement. Will your product be delivered directly to the customer or construction site? If so, your product would be directly subject to the applicable requirement.

But what if your product is being supplied to a higher-tier manufacturer who will integrate into that manufacturer’s own product? Under that circumstance, your product would be at most a “component,” if not a “subcomponent,” of the product actually delivered to the customer or construction site.

The compliance considerations are usually different for suppliers of components or subcomponents. As one example, under BABA, there is no “cost-of-subcomponents” test for components. That means a component of a manufactured product is considered “domestic” under BABA so long as it is manufactured in the United States, regardless of the country of origin of its component parts.2 In that case, your compliance obligation as a component supplier is to report the country of origin of your product to your customer, which will then have to assess whether it can meet the 55% cost-of-components threshold at the “manufactured product” level. Because components do not need to meet a “cost-of-subcomponents” standard, a component supplier would not need to address the domestic/foreign content of its product, only the country in which it is manufactured.

What Does U.S. “Manufacturing” Require?

The Buy American and Buy America regimes both require U.S. manufacturing, but the definition of “manufacturing” is hard to pin down. The term is not defined in the Buy American Act contract clauses themselves, nor is it defined in the statutory text of BABA. It is generally understood to require some type of processing that can be said to convert component parts into the end product sought by the government, but where and how to draw the line can become quite complicated.

The lack of a single definition of “manufacturing” is attributable in part to the variety of types of manufacturing processes. Different sources have articulated different definitions. For example, courts and the U.S. Government Accountability Office have framed domestic manufacturing as completion of the article in the form required by the government or making the article suitable for its intended use and establishing its identity as the relevant end product. Federal procurement regulations define the “place of manufacture” of an item as the place “where an end product is assembled out of components, or otherwise made or processed from raw materials into the finished product that is to be provided to the Government.” These definitions are hardly black-and-white.

As a result, when a product has undergone significant processing outside the United States prior to arrival in the U.S. for final processing, the assessment of whether the U.S.-based processing is sufficient to constitute domestic “manufacturing” typically requires a fact-intensive analysis that evaluates the comparative time, complexity, and value of the processing operations performed in the U.S. and in foreign countries.

Establishing Processes to Ensure Buy America Compliance

The complexity and uniqueness of Buy America requirements places a premium on establishing processes to assess—and document—your ability to comply with those requirements. If you have both U.S.-based and non-domestic manufacturing sites for a particular product line, you need a process to ensure that only U.S.-manufactured products are supplied on a project subject to a Buy America requirement.

If your product will be supplied directly to the customer, assess the material costs of your product to determine whether you can meet the applicable cost-of-components test. This will require engagement with your supply chain to make certain you are obtaining country-of-origin information on your components, as well as identifying what articles are the actual “components” of the product for cost purposes. Keep in mind that the cost-of-components test is essentially a materials cost test that does not include the costs associated with manufacturing the end product from its various components.

If you are supplying products subject to the strict iron or steel sourcing requirements of Buy America, you should institute a process to obtain so-called “step certifications” confirming each step of the manufacturing process occurred within the United States.

Be sure to educate your sales and purchasing teams to recognize and distinguish among the various types of Buy American or Buy America requirements. That recognition is key to ensuring that your quotes or proposals account for the correct set of requirements and that your purchase orders to suppliers flow down any terms needed to ensure compliance. It also will help your purchasing department identify areas in which you may need to seek out alternative suppliers, to be able to meet some of the domestic content thresholds.

Finally, make sure your sales team understands the risks posed by signing certifications of compliance with domestic content requirements. Buy America compliance is likely to be a growth area in false claims litigation, and inaccurate certifications provide potential fodder to government officials and qui tam relators. If your product does not comply with the applicable requirement, it is critical that you not claim that it does. While waivers of the Buy America requirements may be difficult to come by, it is far better to try to pursue a waiver than to face the headaches that would result from a false certification of compliance.

——————————————————–

1 These dollar thresholds are subject to adjustment every two years and are scheduled to be adjusted late this year, with the adjusted thresholds to be effective January 1, 2024.

2 This discussion focuses on the requirements for products that would be considered “manufactured products” under BABA. There would be a need to trace the origin of iron or steel in an iron or steel component of a product considered under BABA to be an “iron or steel product.”

How to Protect Intellectual Property During Product Development

| AUTHORS | |||||

| Andrew J. Salomone | [email protected] | |||||

| Roberto J. Fernandez | [email protected] | |||||

| Scott D. Anderson | [email protected] | |||||

| Marcus W. Sprow | [email protected] | |||||

In this article, we discuss critical intellectual property considerations, including patents and trade secrets, for companies engaging in development of key technology. Covered topics will include employment agreements and onboarding processes for new employees, and joint development agreements (JDAs) with third party collaborators.

Today’s high-tech products require a combination of skills across an array of engineering disciplines. For example, producing electric vehicles requires the integration of manufacturing prowess, electrical brilliance, and software genius. As a result, companies constantly collaborate across disciplines, often resulting in relationships with third parties that are often of a dissimilar industry, location, and maturity. Later disputes with these parties over intellectual property can delay or destroy progress, crippling companies while their competitors succeed. This article provides guidance on avoiding such pitfalls.

Put Intellectual Property at the Forefront of Relationships and Engagements

The first step toward effectively protecting intellectual property (IP) (e.g., patents, trade secrets, trademarks, copyrights, etc.) is to raise the issue before development even begins. This applies to both relationships with new employees and new engagements with third parties (e.g., vendors, suppliers, contractors, etc.). Agreements governing these relationships and engagements should be carefully crafted not only to maintain ownership of IP that existed beforehand (so-called “background” IP) but also to parse out ownership and use of IP that will be developed during the course of the development relationship (so-called “foreground” or “generated” IP). Relationships often change as time goes on, and parties’ views on the value of generated IP may evolve during the course of development, so it is typically easier

IP-Conscious On-Boarding of New Employees

New employees bring fresh ideas to a team, but employers should take steps to educate new employees to protect future IP and reduce risks associated with third-party IP. During on-boarding, new employees should be educated as to the different types of IP with examples of how each type of IP is typically generated. This education should also teach new employees to recognize when their future work generates IP and inform them as to the internal processes the employer uses to harvest this IP. One common practice is for employees to expeditiously submit invention disclosures to an internal “invention review committee” that is responsible for selecting which will be pursued in patent applications and which will be kept as trade secrets.

Part of this education should also focus on effective and efficient documentation of new IP. New employees should be encouraged to save and date any information generated during initial brainstorming of IP and to promptly facilitate harvesting of the IP by the employer.

Another critical teaching point involves providing education on standard confidentiality practices for safeguarding IP from non-employees. To the extent that collaboration with a third party is necessary (a point which is discussed in more detail below), employees should be trained to first confirm that proper agreements (e.g., non-disclosure agreements, confidentiality agreements, joint development agreements, etc.) are in place. Ideally, any IP would be harvested before any collaboration occurs, either by filing a patent application, recording new innovations in a trade secret log, and/or modifying existing agreements as needed.

New employees should also be trained to understand their obligations to their former employers, and their ideas should be screened to reduce the risk of such “IP contamination.” Such policies can help protect against IP claims from the prior employer, such as those for trade secret misappropriation or breach of confidentiality.

The legal language of employment agreements should also be carefully reviewed on an ongoing and routine basis. For example, employment agreements should be drafted to state that employees “do hereby assign” their IP rights to the employer. The present tense language is critical. Other language can be found insufficient to cement the employer’s right to the IP. In addition to keeping legal language up to date, ongoing review of employment agreements will help ensure that they remain focused on the employer’s current and future business interests.

Forging Symbiotic Relationships with Third Parties

Engagements with third parties, often arising in the form of joint development agreements (JDAs), should receive similar care and planning. As with any agreement, carefully drafting terms to achieve specific goals while simultaneously mitigating risk is vital. This is especially the case for JDAs involving the development of key technology with dissimilar collaborating parties. When collaborating parties are differently situated (e.g., established OEM vs. budding start-up), differently located (e.g., domestic vs. foreign), or have different commercial goals (e.g., beholden to shareholders or some particular financial metric), it is imperative to have a carefully crafted JDA that facilitates the creation and protection of key technology.

Defining the Collaboration

As a threshold matter, it is necessary to identify the proper parties involved in joint development efforts. In many instances—even those involving young companies or those new to a particular technological area—multiple separate legal entities can be involved in activities that may yield new intellectual property or require use of existing intellectual property. As a further complication, these legal entities may have obligations to other legal entities. Failing to identify the proper parties could undermine the utility of the JDA. Conducting thorough due diligence is necessary to mitigate risk at this threshold step.

Identification of proper parties can also require an accurate and complete understanding of the scope of work contemplated by the JDA. Specifically, it is important to understand what work will be done and when, who is doing the work, and what IP is expected to be generated. For example, is the work likely to generate entirely new IP, combine existing-but-separate technologies together, integrate existing technology into a new product, or something else? Based on the work to be performed, which party or parties are likely to generate IP?

When completion of the work under the JDA involves use of existing IP of one party, a license may be required by the other party to permit use of the background IP to accomplish the efforts outlined in the JDA scope of work. However, such licenses can extend further into subsequent commercialization of generated IP, such as when use of the background IP is required to use the generated IP. In those circumstances, licensing strategies should ideally be tailored to suit the parties’ intended commercial uses without extending further than necessary. For example, the license could permit certain uses of the background IP, such as producing a product embodying the generated IP for a specific third party, while prohibiting other uses, such as producing another product embodying the background IP for a competitor.

Planning for Generated IP

A robust JDA will be tailored to particular varieties of IP that are likely to be generated by development efforts. Whether the work performed under the JDA will create copyrightable work, patentable ideas, trade secrets, or some combination will impact the terms of the JDA. If the generated IP is likely to be patentable, the JDA should contemplate, among other things, who will own the resultant patent rights, how those patent rights will be secured, who pays for the patent application process, and the extent to which those rights can be enforced or licensed.

If the generated IP will be kept as a trade secret, the terms of the JDA should provide for adequate security measures to properly maintain the trade secret according to applicable state law. This can be complicated if the parties are located in disparate geographic locations or if the parties have disparate internal security policies, which may justify opting for patent protection over trade secret protection. Whatever the case, it is prudent to consider what form any generated IP may take so as to be readily equipped to protect it.

In addition to identifying what generated IP is likely to result, it is important to be cognizant of where generated IP will be created and where it will be used. With regard to patents, for example, certain countries may impose restrictions on foreign filing based on where the invention was conceived, an inventor’s residency, or an inventor’s citizenship. Some jurisdictions may even impose restrictions on how generated IP can be secured. When possible, companies would be wise to plan ahead for how to address these hurdles.

Establishing Ownership of the Generated IP

To avoid unnecessary complications in procurement and later use of generated IP, a JDA should comprehensively define ownership of generated IP. In most jurisdictions, patent rights in an employee’s invention initially belong to the employee. Employers typically gain patent rights to their employee’s inventions by employment agreement or assignment. During joint development, when employees from both parties are inventors, both parties will have likely obtained rights in the invention from their respective employees. Without a further agreement, both parties will be joint owners of any resulting patent.

While joint ownership can ensure access to the IP, it can present several administrative or logistical difficulties. For example, when generated IP includes patentable ideas, disagreement between joint owners as to procurement, maintenance, defense, or enforcement of patent rights can materially affect the value or utility of the generated IP. This can be especially true when the jointly developing parties belong to different industries or are affected by different motivations or pressures. In the U.S., for example, each joint owner can use the patent, or sell or license their rights in it, without the approval of the other. Further, all joint owners must consent to any patent infringement suit based on the patent.

For these reasons, when available, sole ownership of generated IP may be preferrable to ensure maximum value and utility of the generated IP. For example, sole ownership more readily enables harvesting IP in a manner that will yield commercially-relevant assets. Risks to the non-owning party can be mitigated by including provisions in the JDA imposing an obligation to diligently prepare IP or by otherwise creating some other mechanism for a non-owner to influence a sole owner’s control of the generated IP.

Using the Generated IP

Beyond ownership considerations, a JDA should be crafted to include appropriate provisions to govern use of the generated IP. Typically, JDAs include licenses to generated IP (and background IP) owned by the other party for the duration of the joint development efforts. JDAs may also include restrictions on the use of generated IP by the owning party (whether jointly or solely owned). In some cases, licenses and restrictions can also extend to subsequent commercialization of generated IP. When commercial goals diverge, licenses and restrictions can mitigate risk by permitting only appropriate uses of the generated IP by appropriate parties. Licenses to generated IP should consider implications of subscription-based commercialization models, which has become increasingly popular with the proliferation of software in manufacturing-centric industries.